By Chris Agbedo

There are questions in the life of a nation that are asked not because answers are unavailable, but because the answers, though visible, refuse to submit themselves to public reason. Such questions hover uneasily between inquiry and indictment. They begin as requests for clarification and end as mirrors held up to power. In Nigeria, a peculiar category of such questions exists—questions that over time shed their interrogative innocence and harden into rhetorical fossils. They are repeated not in expectation of resolution, but as ritual reminders of a state’s moral inertia. Foremost among them is the haunting refrain: Who killed Dele Giwa?

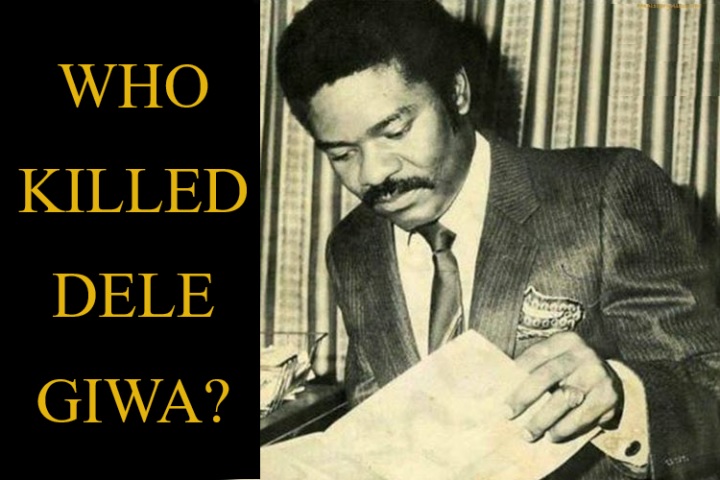

Thirty-four years after Dele Giwa—crusading journalist, founding editor of Newswatch, and one of the sharpest pens of Nigeria’s Fourth Estate—was killed by a parcel bomb delivered to his Ikeja home, nothing of consequence has been established beyond the fact and the grotesque ingenuity of the murder. The question has outlived governments, outlasted transitions, and survived the mortality of many of the actors who once strode the Nigerian stage with swagger and impunity. It remains unanswered not because it is unanswerable, but because answering it would require the Nigerian state to look into a mirror it has consistently chosen to avert its gaze from.

In the immediate aftermath of Giwa’s assassination, the editors of Newswatch, led by Ray Ekpu, converted grief into a quiet but radical editorial practice: every weekly edition carried, pinned permanently on its front page, the question—Who killed Dele Giwa? It was journalism stripped to its moral core. No embellishment, no accusation, no speculation. Just a question. A simple interrogative that slowly acquired the weight of an indictment precisely because it remained unanswered. When the question was eventually pulled down, it was not because an answer had emerged, but because the ritual itself had exhausted its power to shame a state that had perfected the art of not blushing. Yet, another dimension to the abrupt end to the editorial riposte alleged subtle threats from the authorities, which effectively drew the attention of Dele Giwa’s grieving colleagues to the wisdom of the Igbo proverb, one that points to the danger of premature retaliation against the killers of one’s father. “Nwata etoghi eto jụwa ihe gburu nna ya,” as the saying goes, “ihe ahụ gburu nna ya ewere isi ya.” (A child in a hurry to avenge its father’s death risks suffering father’s fate). An Ezikeọba proverb caps it all with a clincher rhetorical question: Does it make any sense for a woman to appeal to her life-force (chi) to take her life all in the process of mourning the death of a co-wife? (Oonye ọ na-akwakọnụ nwunye ji ye sị chi ye chọta a?)

Yet Nigeria, it seems, has not exhausted its capacity for producing new mystery questions. Some three and a half decades after Giwa, two unsettling questions have joined that grim archive. “Who gave the order to withdraw the troops overseeing the security of Government Girls’ Secondary School, Maga, in Sokoto, shortly before terrorists attacked and abducted 24 girls?” And, more recently, “who altered the Tax Reform Bills passed by the National Assembly before presidential assent?” At first glance, these questions appear different in gravity and genre—one rooted in blood and terror, the other in bureaucratic legerdemain. But beneath their surface dissimilarities lies a common pathology: the systematic evacuation of responsibility from the public realm. In each case, the question seems obvious enough to demand a straightforward answer. Orders are given by people. Bills are altered by hands. Decisions have signatures, trails, and beneficiaries. Yet, in Nigeria, the obvious has a strange habit of becoming elusive. This is where mystery questions cease to be about facts and begin to reveal something more troubling about the architecture of power.

Philosophers have long argued that political authority is sustained not merely by coercion but by intelligibility—the ability of citizens to understand, who decides what, and on what grounds. Hannah Arendt warned that the banality of evil often lies not in monstrous intent but in the routinisation of unaccountable power. Nigeria’s mystery questions dramatise this insight. They are symptoms of a system in which power acts, but refuses to speak; decides, but declines to explain; kills, alters, withdraws, yet leaves no authorial trace. Take the Maga schoolgirls. In a country traumatised by Chibok, Dapchi, Kankara and countless unnamed tragedies, the presence of troops around a vulnerable girls’ school was not accidental. It was a recognition—however belated—that the state bore a duty of care. Their sudden withdrawal, shortly before an attack, is therefore not merely a tactical error; it is a moral rupture. To ask who ordered that withdrawal is to ask where responsibility resides when protection is knowingly removed. The silence that follows such a question is not neutral. It is an answer of sorts—an answer that says accountability is negotiable, and lives are collateral.

The Tax Reform Bills episode, though bloodless, is no less revealing. In constitutional theory, the passage of a bill by the legislature and its assent by the executive is meant to be a transparent choreography of democratic authority. To suggest that what was assented to and officially gazetted was not what was passed is to open a chasm beneath the very idea of representative governance. Here again, the question—who altered the bills?—should have a mundane answer, traceable through legislative proceedings – clerks, drafts, versions, and signatures. Its persistence as a mystery signals something deeper: a state in which documents can mutate without authors, and power can rewrite outcomes without owning the act. Nigeria’s mystery questions thus function as what the philosopher Paul Ricoeur might call wounded narratives—stories interrupted at the point where meaning should crystallise. They refuse closure, and in doing so, they keep reopening the ethical wound of the polity. Each unanswered question accumulates symbolic weight, teaching citizens, subtly but firmly, that truth is optional and responsibility fungible.

Over time, these questions stop being asked in hope. They are asked in irony. Who killed Dele Giwa? has long ceased to be a request for information; it is now a shorthand for the state’s enduring allergy to self-incrimination. It is a way of saying: we know that you know, and you know that we know; yet, we all proceed as if everything is normal and ignorance were a shared convenience. This is the most corrosive effect of mystery questions. They normalise cynicism. When a society internalises the expectation that no one will ever be held to account for the gravest acts, public morality withers. Law becomes procedural rather than principled. Institutions persist, but legitimacy evaporates. The state continues to speak, but its words sound increasingly hollow, stripped of the authority that only truth can confer.

And yet, mystery questions endure precisely because they still carry a residual moral charge. They are asked because something in the collective conscience refuses to be fully anesthetised. They are Nigeria’s way of remembering, of refusing complete amnesia. In this sense, every repetition of Who killed Dele Giwa? is an act of quiet resistance—a reminder that unresolved injustice does not expire with time. Perhaps, this is why new mystery questions keep emerging. A society that has not resolved its foundational riddles is condemned to reproduce them in new forms. The unanswered past leaks into the present, reshaping it in its own image. The bomb that killed Giwa and the pen(s) that altered a bill belong to different worlds, but they are animated by the same logic: power without confession. The true tragedy, then, is not that these questions remain unanswered, but that the Nigerian state appears to have made peace with their permanence. A nation that learns to live with such questions risks mistaking endurance for stability and silence for order.

Yet questions, by their very nature, are restless things. They do not die when ignored; they only retreat. They wait. They age. They gather moral sediment. And sometimes, long after the actors have exited the stage, long after the applause and the denials have faded, they return with an insistence that can no longer be deferred. History, unlike power, is patient. It has a stubborn habit of reopening files that authority thought it had buried under layers of silence, fear, and official forgetfulness. This is precisely why who killed Dele Giwa refuses to expire.

Writing under the evocative caption, Again, Who Killed Dele Giwa?, Olatunji Dare had observed in The Nation newspaper (27 February 2024) that the question has resurfaced with renewed force, not as mere nostalgia or journalistic ritual, but as a live constitutional and moral challenge. The Incorporated Trustees of Media Rights Agenda, acting as institutional memory for a country prone to amnesia, breathed fresh life into the question through a petition before the Federal High Court in Abuja. In a rare moment when the law itself appeared to clear its throat, the presiding judge, Justice Inyang Ekwo, reportedly directed the Attorney General of the Federation to bring Dele Giwa’s killers to justice, holding that the assassination violated the right to life as guaranteed under the Nigerian Constitution and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

For the first time in a long while, the question did not merely echo in newsrooms and private conversations; it found its way into the austere language of judicial obligation. Dare, in his characteristically restrained but piercing manner, ended with a question that now hangs heavily in the air: Is this finally the momentum the attentive public has been yearning for? It is a question layered upon a question, a meta-interrogation that exposes Nigeria’s peculiar tragedy. For decades, the country has not lacked facts, suspects, insinuations, or even whispered certainties. What it has lacked is the courage to allow truth to complete its journey from knowledge to acknowledgment, from suspicion to accountability. And so Who killed Dele Giwa? became less a query than a moral barometer, measuring how far the state was willing to go in protecting itself from its own reflection. But Nigeria, being Nigeria, has always understood the language of parable perhaps better than the language of policy.

Gentleman Mike Ejeagha, the unassuming philosopher-minstrel of Igbo folklore, once sang that the stub of a plantain thrown into the sea does not simply dissolve into oblivion. Somehow, against expectation, against logic, it takes root in deep waters. In time, it rises, towers, and blossoms into luxuriant foliage. The song is not about botany. It is about truth; about how what is discarded, submerged, or deliberately forgotten retains a stubborn capacity for resurrection. Truth, Ejeagha reminds us, does not depend on favourable conditions to survive; it merely waits for time to ripen. So it has been with Nigeria’s mystery questions. Jim Nwobodo, former governor of old Anambra State under the Nigerian Peoples Party (NPP), stumbled into philosophy under the harsh tutelage of political injustice. Allegedly rigged out of the 1983 elections, he distilled his frustration into a sentence that has since migrated into proverbial lore across Igbo land: E mecha, eziokwu ga-apụta ihe—in due course, the truth shall surely prevail. It was not a threat. It was not a prediction anchored in optimism. It was a statement of faith in time itself as the ultimate adjudicator.

To be continued.