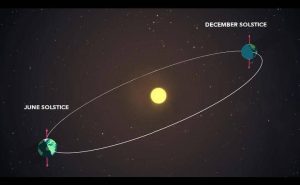

As the Northern Hemisphere approaches the height of summer, Earth has just reached the farthest point in its yearly orbit around the sun.

At precisely 3:55 p.m. ET on Thursday, the planet arrived at a position known as aphelion, the moment when Earth is most distant from the sun.

This point places our planet about 3.1 million miles farther from the sun than it is at its closest approach in early January, a position called perihelion.

Despite this increased distance, approximately 94.5 million miles, much of the Northern Hemisphere continues to endure intense heat.

This apparent contradiction often leads people to ask: If we’re farther from the sun, shouldn’t it be cooler?

According to Diaspora Digital Media (DDM), while it may seem intuitive to link warmth to proximity, the Earth’s seasonal temperatures are not primarily governed by its distance from the sun. Instead, the dominant factor is the tilt of Earth’s axis.

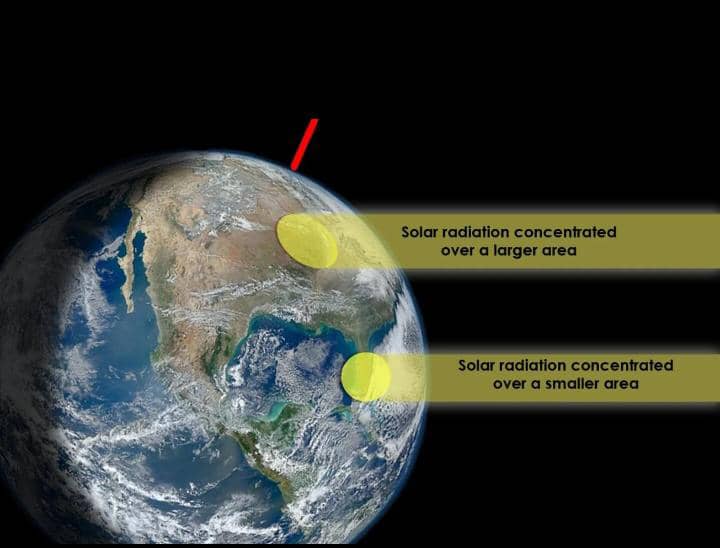

Earth rotates at an angle of 23.5 degrees, and this axial tilt determines how much sunlight different parts of the globe receive at different times of the year.

In July, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the sun, resulting in longer days, higher sun angles, and more direct sunlight, all of which significantly contribute to summer heat.

While Earth’s orbit is slightly elliptical, the difference between aphelion and perihelion represents just a 3.3% variation from the average distance of 93 million miles.

This change causes only about a 7% drop in the solar energy reaching the planet, a relatively minor effect when compared to the impact of axial tilt.

The difference in sunlight due to tilt is striking. Cities around 30 degrees north latitude, including Phoenix, Houston, and New Orleans, receive more than twice as much solar energy in summer than in winter.

Farther north at 40 degrees latitude, cities like New York, Denver, and Columbus experience an even sharper contrast, with solar radiation increasing from about 145 watts per square meter in winter to 430 in summer, nearly a 300% rise.

This dramatic difference highlights the overwhelming influence of Earth’s tilt on seasonal weather.

Even as the planet moves farther from the sun, its orientation ensures that the Northern Hemisphere remains bathed in powerful, direct sunlight.

In the end, it’s not our distance from the sun that makes summer feel like summer, it’s the angle at which we face it.