By Sani Saidu Muhammad

For Over 11 communities in Kano State, North-West Nigeria, farmers and residents are grappling with thick smoke emitted by nearby factories, which has damaged their crops. The Jakara and Challawa streams have reportedly been contaminated. In this report, Sani Saidu Muhammad explores how industrial flaring and waste have impacted local communities, damaging livelihoods and health.

It was a serene afternoon in May with a sunny cloud in the Kadawa community. Fatima Aliu, a middle-aged farmer in Kano State, who specialises in farming went to her farm early one morning to saw her crops blackened by smoke emissions from nearby factories of Mamuda Agro, Allied Products Nigeria Ltd & African Textile Manufacturers Limited and Honey Plastics Nigeria Ltd.

The grandmother of five is one of thousands of Kadawa residents affected by smoke emissions from nearby factories. She says the pollution has made it harder to grow food and care for her grandchildren.

Mrs Aliu is hapless and frustrated. Her situation is worsened by difficulty in preventing flaring from the companies close to her which frequently damages her crops—her primary means of livelihood.

All that is left for Mrs Aliu is memories of her bountiful harvest.“I remember bumper rice harvests – now. The river water is brown; our maize tastes of chemicals”.

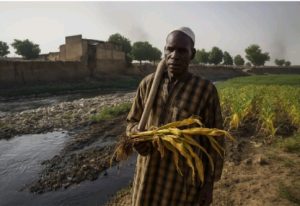

Another victim of the disaster is Mallam Ahmad Mukhtar Gezawa whose farm is also affected by the poisoning stench from companies working on textiles.

“Our soil has turned toxic,” he says, echoing a warning whispered from village to village.

However, Kano’s unchecked industrial pollution is devastating its farms, poisoning lives and threatening both the state’s and Nigeria’s food security.

Kano State, in Northwestern Nigeria, is now home to roughly 20 million people. As Nigeria’s most populous state and a key hub of industry and agriculture, Kano is second only to Lagos in manufacturing output, yet more than 70% of its economy and half its people depend on farming.

But at dawn over the Sharada, Bompai and Challawa industrial zones, the reality is grim. Massive chimneys belch thick, acrid smoke over cracked rice paddies and irrigation canals, and untreated wastewater pours into the Jakara and Challawa rivers. Poisoned water infiltrates wells and soils; crops wither as if burned by an invisible fire. Farmers who once harvested abundant crops now tread warily amid this toxic haze.

Poisoned Air and Water: Industry’s Toll.

Kano State’s industrial zones once promised jobs and growth. Now their legacy is one of contamination. Bichi (2013)documented 320 factories packed in urban zones, ranging from tanneries and textiles to oil processors. Virtually none treat their waste. Professor Salisu Bichi while dialoguing with this reporter said many industries in Kano do not have wastewater treatment facilities.

“Most of these industries do not have wastewater treatment facilities and thus discharge untreated effluent into adjoining receiving water bodies”, he said.

Raw tannery and textile waste flows through storm drains into the Challawa River, while another canal carries Sharada’s tannery effluent into nearby farmland. In a direct interview with this reporter, Engineer Abubakar Musa, an environmental project manager, said his team had tested the river silt. “We’ve measured chromium and lead in the river silt at three to five times the Nigerian safety limits,” he said.

The Companies Confirms of Polluting the water.

Abdullahi Gambo, a former waste supervisor in Sharada Tanneries was initially reluctant to speak. He declined to answer several questions posed by this reporter. “We knew the pipes discharged raw waste directly,” he said before declining to further address questions asked by this reporter.

“We were told not to speak, not to question it. Managers said, ‘The river washes it away”, he said.

A source in the Sharada Tanneries who pleaded for anonymity told BluePrint that they had to flush out untreated chemical waste into canals. In his words, he said, “During night shifts, we flush untreated chemical waste straight into the canals. It’s common knowledge. If you report, you’re fired.”

A factory foreman, Yakubu Idris, confirmed that the practices had been a traditional but he was not allow to speak over the lingering effects. He said,“Sometimes I wonder if we are slowly killing people downstream. But my job depends on silence.”

Maryam Hassan, a former administrative officer at a plant in Sharada, stated: “We had meetings where management openly said any budget for treatment facilities would be slashed. The profits mattered more. Even when workers complained of headaches or rashes, they blamed the weather.”

A senior civil servant in the state under the Ministry of Environment who preferred not to be named said the practice would continue as the factories have godfathers and would be difficult to stop.

“Some factories have godfathers. When we tried to enforce closures, a call would come from above. We felt helpless, demoralized. It’s not just neglect, it’s protected impunity”, he said.

Authorities have occasionally acted. In 2021 NESREA (the federal environmental agency) shut down 12 Kano factoriesfound in breach of pollution laws. Director General AliyuJauro warned that “despite repeated sensitization, some industries have refused to comply with…environmental regulations”. But enforcement is spotty. “The fines are small and delays long,” says lawyer Chikwe Ani of the Nigeria Environmental Rights Alliance.

NESREA’s tour of Kano leaves farm fields downstream of factories unremediated. A recent state government report confirms unsafe conditions: Sharada Market, Ja’en and Gaida neighborhoods all showed “poisonous air” levels during a May 2025 survey, and Bompai’s canals still run murky with chemical odors(ammonia levels 2–3× above norms).

Marketers reject poisoned foods, farmers lament.

Several supermarkets across Kano State reject farm produce from their village, fearing poison from water. Such market rejections have cut rural incomes and pushed families into debt.

“Supermarkets have started rejecting produce from our village”, a local grain miller, Aisha Sadiqu said. “If heavy metals are detected even slightly above the limit, shipment is discarded,”..

Ibrahim Sulaiman, a mechanic near Sharada, says black soot speckles his roof every dawn. “Our children wheeze and we fear for their lungs, “he pleads.

Experts speak up on factories damages

As toxins seep into fields, Kano’s rural foodbelt feels the impact. Cadmium and chromium accumulate in soils watered by factory drains, studies find.

Hasan Bichi, a soil scientist at Bayero University has traced heavy metals in farm plots of the affected communities in the state.

He says: “Vegetables grown in irrigation from Challawa showed Cd and Cr levels above safe limits, threatening human health”.

Another experts in Kano State Polytechnic, Aliya Miko reviewed decades of data and concluded that “using contaminated water for irrigation…leads to heavy metal buildup in soils and crops

Farmers in Minjibir and Giwa (downstream of industrial run-off) report dying palm trees and withered rice, consistent with the toxicology.

A 2023 survey of Kano farms found alarming contamination: cadmium, arsenic and lead in vegetables regularly exceeded WHO/FAO safety levels. The cassava, okra and tomatoes from Sharada-area farms had bio accumulated these metals far beyond guidelines. “We test our tubers now,” says farmer Hassan Danladi.

Dr. Maryam Abdullahi, an agronomist at Bayero University, connects water pollution in the areas to factories working in the affected areas.

She said that heavy metals in irrigation water are absorbed by plant roots.

She noted: “Heavy metals in irrigation water are absorbed by plant roots; they stunt growth and remain in the grains. This creates a chronic food safety problem”. She and others urge regular testing: the Kano-State Poly review recommends “monitoring heavy metals in soils and crops…and guidelines for safe cultivation on contaminated soils”.

Satellite data confirms spikes in NO₂ over Kano on working days. (Globally, satellites show African urban NO₂ is climbing faster than in rich countries.) Local youth have even launched DIY monitors: the “Kano Skywatchers” group uses low-cost PM sensors and open-source mapping to track hotspots. Their AI-assisted map (trained on NASA air-quality data) highlights Kumbotso and Bompai as areas of worst exposure. Leveraging Google Earth Engine, they overlay factory locations with diminished vegetation indices, finding correlations between smoke plumes and crop stress.

Voices from the fields.

Smallholder farmers and community activists have become whistleblowers. Aisha Mamman, a grandmother tending herbs near the Challawa River, recounts: “I saw the fish die a few years ago, water smelled like chemicals.” She now treats her well-water and gardeners test cabbage leaves with a homemade kit. University researchers like Sani Ibrahim (BUK) back these accounts: his 2022 fieldwork found nitrates and cadmium in Minjibir irrigation ponds at multiples of WHO “safe” levels.

Farmers tell of market bans too: “Last month I took yams to Danbatta market and they said the tubers were bitter,” says farmer Jibrin Yusuf. Chemical analysis (our team learned) traced those toxic flavors to chromium runoff from a nearby dye factory. Another whistleblower, Shaibu Garba, a former mill manager, alleges one mill recorded heavy metal levels eight times above WHO limits when processing Kano rice. Anonymously he notes, “Even the government-imported rice sometimes ships back for testing; ours doesn’t even get a look.”

Regulation and reform: too little, too late?

Legal analysts and NGOs say Kano’s plight is rooted in lax enforcement. NESREA’s 2021 crackdown was cheered, but Activist Ibrahim Musa of the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre says follow-up is weak.

The Environment Protection Act has teeth, but neither NESREA nor the Kano State Environmental Agency impose real penalties. Violators pay fines they can afford and keep polluting,” he argues.

Even within the government, priorities conflict: the old Sharadatanneries were nationalized for jobs at the expense of cleaning up waste. Today, Prof. Bashir Adamu of BUK cautions that “effluent limits exist, but compliance monitoring is sporadic, and self-reported data from industries is often unverified.”

Experts on policy propose remedies. They cite Nigeria’s own standards: NESREA’s water quality limit for lead is 0.01 mg/L, yet samples in Kano are much higher. They urge a two-pronged solution: stricter monitoring by empowered regulators, and investment in remediation. International donor programs are already working in northern Nigeria on bioremediation: one pilot uses sunflowers to extract heavy metals from fields.

Legal scholar Ngozi Udofia notes that Nigeria’s 2018 Environmental Impact Assessment Act mandates community right-to-know and penalty clauses for breaches – tools Kano regulators have barely used. Civil society groups now push for mandatory environmental audits of factories and citizen “watchdog” apps to report spills (in NESREA’s words, the public should act as “environmental watchdogs”.

Sani Saidu Muhammad can be reached via sanisaeed366@gmail.com

This article was supported by the Africa-China Reporting Project based at the Wits Centre for Journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.